Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Despite being a spontaneously growing plant (meaning not planted or maintained,) the paulownia tree on Bergen Street is documented on the NYC Street Tree Map website, erroneously identified as a flowering dogwood. When this individual was recorded in the 2015 tree census, it had a diameter of 8 inches and it was determined that each year it intercepted 423 gallons of stormwater, conserved one pound of energy, absorbed 486 tons of carbon dioxide, and provided $69.77 in benefits. Flowering dogwood or not, it is uncontested that this paulownia tree and other spontaneous urban plants provide ecosystem services. However, it is also clear that this aggressively resourceful plant causes some problems as well. In this paper, I will explore the reasons why this species thrives in an urban environment and what its presence might mean to both the city and its forested outskirts.

Paulownia is endemic to Asia. In Japan, the tree is considered both closely connected with female identity and with royalty. It was a tradition to plant a paulownia tree, or in Japanese a kiri, upon the birth of a baby girl. The tree would grow tall quickly and would be ready to cut down when the girl reached the age to marry. The wood was then used to build a box for her dowry. Paulownia wood was regarded as being of high quality and suitable for storing fragile kimono and other silk garments. The paulownia tree has other traditional significance in Japan. The use of paulownia as a seal is called a Kirimon [figure 5]. Initially the Kirimon was used by the Japanese imperial family. Since the Meiji Period (1868-1912), the Kirimon became the emblem of the prime minister and the symbol of the Japanese government. The use of paulownia as a symbol was inspired by Chinese mythology, which associates the tree with the phoenix due to its ability to regrow after being chopped down [figure 6]. In both China and Japan the lightweight, finely-grained wood is used for musical instruments and ornamental carving.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Paulownia trees were introduced to Europe in the 1800s, imported by the Dutch company from India. It was named paulownia after the Russian noblewoman Anna Pavlovna. It was prized for its fast-growing high-quality hardwood and was purposefully spread throughout Europe. It is believed that paulownia trees were introduced to New York when its seed pods were used as packing peanuts to transport Chinese porcelain from Europe [figure 7]. It has also been intentionally grown in the U.S. for ornamentation and for silviculture. It makes a useful farmed tree since it grows so quickly, is very lightweight, drought- and pH- tolerant, prefers organics-weak soil, and spreads quickly through suckering.

Figure 7.

Growing out of a concrete corner at the edge of the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, right by the Union Street Bridge, is a mature paulownia tree [figure 8]. Upon this tree hangs a sign, which reads: “Paulownia Tree -The lightest hardwood in the world! -Often called the ‘Aluminum of Timber’ -Used to make surfboards + skateboards + guitars -Can grow twenty feet in one year! -Technically an invasive species oh well!” It is a large tree, its branches spreading horizontally over the canal, its bark dark and covered in lichens [figure 9]. It is probably the oldest paulownia tree I have seen in person. Not all paulownia trees in Gowanus look quite as majestic. They usually look like weeds, and this is most likely because most of the individuals spotted in the concrete jungle are less than 10 years old and over thirty feet tall, not to mention growing out of a chain-link fence on a derelict street.

Figure 8.

Figure 9.

Exploring Gowanus at the tip of the canal in early spring, I identified countless paulownia trees. It was a challenge due to the fact that none of them have grown any leaves yet. Adults are easy to recognize while they are leafless due to their dried-up seed pods which remain in place throughout the winter. Juveniles less than 5 years old, however, have not reached reproductive maturity and need to be identified by other clues. I looked for their signature spotted bark and hollow pith (for those with broken or cut branches and trunks). The vast majority of paulownia trees that I found were along fences [figure 10]. Fences provide a unique habitat type for urban plants. They provide shelter for seeds and can act as trellises for vines. These fences usually border unmaintained lots, which can be unpaved, granting access to the soil. If they are paved, there are usually open areas where the fence is staked into the earth and these are places where plants can exploit.

Figure 10.

Two of the defining features of urban environments are that they are full of impervious surfaces like concrete and asphalt, and the heat island effect which results from such surfaces. The heat island effect is when cities are warmer than their surrounding rural areas. The difference is usually 3 degrees Celsius but it can be a much greater amount at night with 12 degrees difference. Concrete and asphalt absorb extra heat from the sun, and there are less plants to release heat through evapotranspiration. The warmth of cities has two implications; one being that it makes it more challenging for native species to live in them, and the second being that cities provide a window into the future of global warming. Aside from absorbing heat, concrete and asphalt also have a large effect on the hydrology of the city. They cause more runoff and compaction of soil and leave less opportunity for plants to grow.

A third defining characteristic of urban areas is that they undergo a large amount of disturbance. Disturbance in the context of ecology is defined as an event that causes great change and/or stress to an ecosystem. The city is always changing- construction and maintenance is regular, as well as pollution and the movement of cars and human bodies. Because of this, spontaneous vegetation in urban areas usually needs to be plants that evolved to grow within disturbed area. However, there is a reason that not many paulownia trees can be found in an urban environment like Manhattan, and in some areas of Brooklyn. Much of the city is too disturbed for many spontaneous trees to establish. Areas that are usually regularly maintained with no large open spaces that are left alone are not places large spontaneous trees are likely to be found. Neighborhoods like Gowanus within that sweet spot of being disturbed but neglected enough for trees to exist unplanned for quite a few years – at least for now.

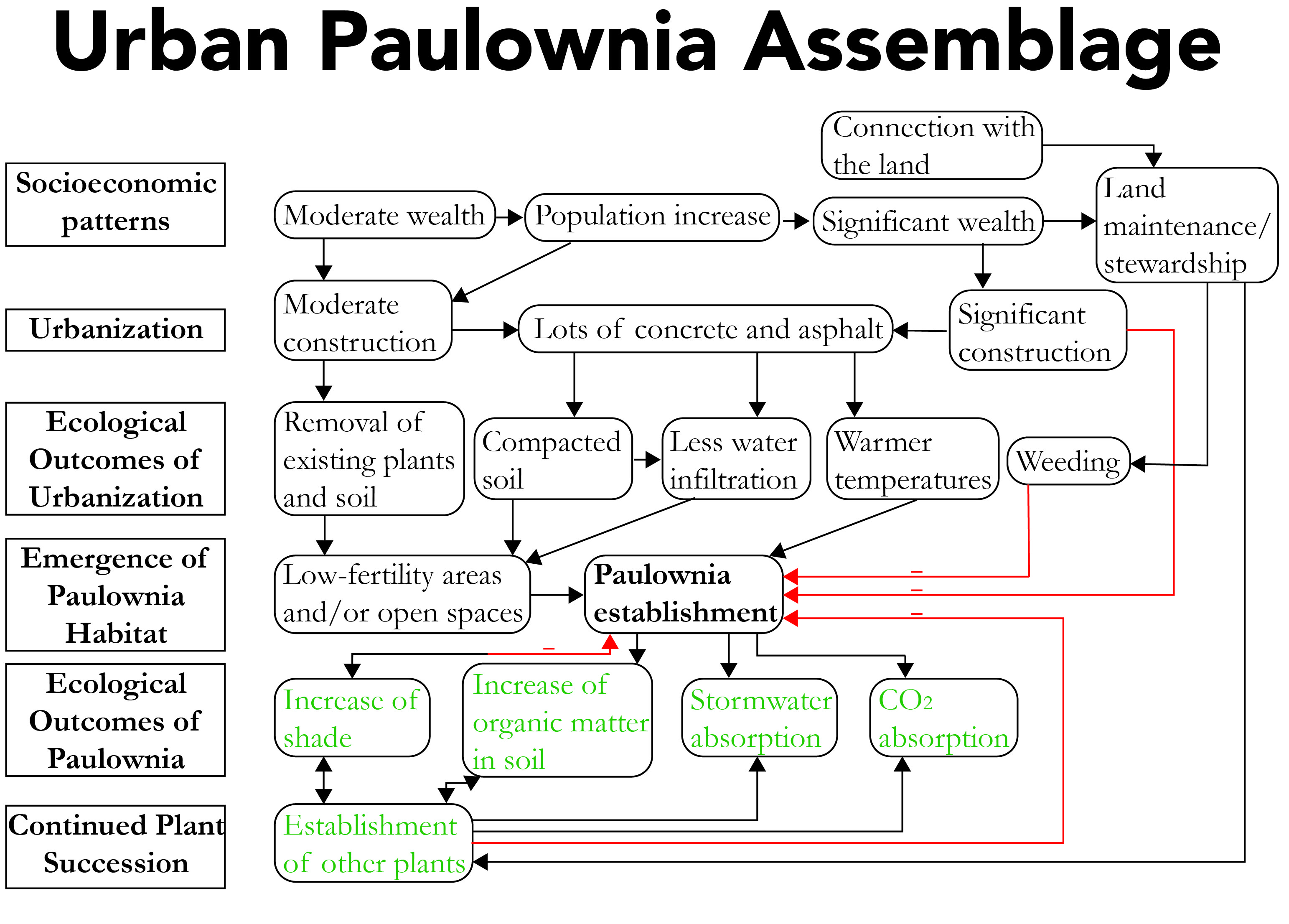

Paulownia trees thrive in disturbance - they don’t mind relying on tiny, polluted, compacted amounts of soil available through cracks in the pavement, and they are endemic to warm regions. They have a few characteristics that make them generally hardy and generalist like drought tolerance and a wide soil pH range, but they are also “preadapted” to the Brooklyn environment, meaning they have evolved traits in a different ecosystem that are also adaptive in a novel environment. They evolved to be early successional trees that are the first plants to germinate in an ecosystem after a disturbance like a fire. They produce millions of tiny winged seeds that travel by wind [figure 11]. Those that are buried deep beneath a layer of humus in the soil’s seed bank can remain dormant for years. After a fire burns the existing vegetation and fuel on the soil surface, the paulownia seeds are exposed to enough sunlight to germinate. They grow tall quickly, producing leaves much larger than they will in adulthood. Within their native habitat, their establishment then encourages the growth of other species. Paulownia trees do not do well when competing for light and will die upon being overshadowed. See figure 12 for an assemblage diagram of this plant’s relationship with the urban environment.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

The purpose of paulownia trees in the urban ecosystem is not so clear, and even less clear in the forested outskirts of the city. Paulownia trees are prevalent in the city’s natural areas and they are considered by NYC Parks to be a priority to remove. Even though some are shaded out, many reach maturity in heavily disturbed areas and pose a threat to the functioning of native ecosystems. As explained earlier, paulownia trees are very successful in infiltrating soil seed banks. NYC Parks conducted a study in which they collected soil samples from various New York City forests and germinated the seeds present in the samples’ seed banks, and paulownia were found in a high percentage of the samples.

Although paulownia is an aggressive, invasive plant that wreaks havoc on forest ecosystems, within the urban context the biggest threat they pose is to the sidewalks. They are growing in places where few other trees can grow. And it’s true - they do provide us services, which include decreasing air pollution, reducing runoff, absorbing excess nutrients, heat reduction, erosion control, soil remediation, and food and habitat for wildlife. They also provide shade for people and greenery. But there is the question of whether we have much choice in the matter. As long as these spaces of low maintenance exist within the city, paulownia will take root. It’s fitting that so many paulownia trees can be found in one of the most disturbed and neglected parts of Brooklyn- the Gowanus Canal [figure 13]. The canal is a relic of an industrial era, a body of water surrounded by a crumbling rectangular border containing sewage waste outfalls, and floods over in the occasional serious storm. And yet, it is always occupied by pairs of geese and other migratory waterfowl. Its surrounding graffiti-covered industrial lots are the perfect home for interstitial plants.

Figure 13.

Urban areas are also increasing. This means that more and more people rely on the urban environment as the regular interface between themselves and the world. Because of this, it is important that we find ways to better cohabitate with the plants that like to live with us, not just for the ecological services they provide but also as actants in a landscape we appreciate and interact with. Spontaneous urban plants, or weeds as they are called, intrinsically provide the benefit of existing without any human intention or maintenance. In this sense, they can be considered self-sustaining.

Tree cover in U.S. urban areas has been declining in recent years, and at the same time the amount of impervious surface is increasing. There are many reasons why trees may be declining in cities. In general, life as a tree in an urban environment requires some hardiness. The soil is polluted and compacted, there is usually trash and dirty runoff, the tree pits are often too small, dogs like to pee on them, they require maintenance that is sometimes too expensive, and often the public is not aware of the correct way to care for them (for example, people piling their trash on the tree pits, or piling mulch and soil too high up on the trunk and killing it). The less trees we have and the more impervious surfaces we construct, the hotter the city may become, a problem which will increase along with global warming. This puts stress not only on the city residents but on the existing vegetation, some of which may be native.

While we are losing so many trees and placing a lot of resources on maintaining them, perhaps we should place our attention on the trees that require zero maintenance to survive in urban environments. Botanist and spontaneous plant defender Peter Del Tredici provides an argument for the importance and role of weeds within changing and human-dominated environments. He challenges the concept that restoration efforts should be focused exclusively on bringing back ecosystems by removing invasive species and replanting native species. Humans have changed environments so much, that weeds are often symptoms rather than harbingers of ecological change. Sometimes a nonnative species will be opportunistic and adaptive enough to thrive in a disturbed environment and provide essential ecological services as a result. He writes that Landscape architects “need to acknowledge that a wide variety of so-called novel or emergent ecosystems are developing before our eyes. They are the product of the interacting forces of urbanization, globalization, and climate change.” Del Tredici argues that spontaneous urban vegetation can achieve many goals of traditional restoration with less financial investment and a greater chance of long-term success.

There are ways we can work with the presence of paulownia and increase its ecological and social values. In Joan Iverson Nassauer’s paper “Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames” she writes about the cultural baggage that influences how we perceive plant ecosystems. People are more likely to not care for a landscape if it looks like it was not cared by others. For example, a neatly mowed lawn with trimmed bushes and flowers behind a white picket fence is perceived very differently compared to a lawn full of a diversity of wildly growing, untrimmed plants. The latter may be more likely to be littered or considered a blight in the community, or even as dangerous. This is an important factor when it comes to creating an environment within a city that encourages people to feel safe in their community. Nassauer explains that there are ways to take a landscape full of messy-looking but important ecological functions and add “cues of care” to elevate their social status and communicate with the public that its existence is valued. Some of these cues can be bird feeders, large flowers, bold patterns, and ornaments.

There are tree breeding companies that see the benefits of paulownia trees and have bred hybrids of both P. tomentosa and other species within the genus (that are not as invasive), that keep the qualities that make it useful for restoration, remediation, lumber, and beauty while controlling its reproductive rates [figure 14]. Because of their incredibly fast growth, they are some of the best plants at sequestering carbon. These breeds are grown in rural areas for their use as biomass and wood, but perhaps there can be cultivars that are bred specifically for the urban environment that provide ecosystem services and beauty in infertile soil while also being easily controlled reproductively.

Figure 14. (Image not by me)

The history of the paulownia tree, as well as of many other plant species considered to be weeds, shows us how the cultural and environmental context determines its value and position in society. The term “weed” is not biological. Weeds are boundary-defying, and their roles are defined not by their intrinsic biology but by their interactions within their environments. There are very real reasons why paulownia trees are considered to be invasive. However, it is important that our perspective of various nonnative species is open and nuanced. Paulownia is likely to be a species that takes habitat with us whether we like it or not, but its role within our city is flexible and evolving. We can take what we know about its history and biology to rethink and reshape our relationship with this plant. Our cities and the planet as a whole will continue to change, and the climate will continue to warm, so the migration of species is inevitable. Paulownia trees have the agency to exist in a habitat that suits them, and we have the agency to decide what this means for us.

Sources

Tredici, P. Del (2020). Wild urban plants of the Northeast: A field guide. Ithaca, New York: Comstock Publishing Associates, an imprint of Cornell University Press.

Tredici, P. Del (2017). From: Living in the Anthropocene : Earth in the Age of Humans, pp. 58-61 ; edited by W.J. Kress and J.K. Stine; 2017, Smithsonian Books, Washington DC . 58–61.

Tredici, P. Del (2014). The Flora of the Future. Places Journal, (2014). doi:10.22269/140417

Tredici, P. Del (2010). Spontaneous Urban Vegetation: Reflections of Change in a Globalized World. Nature and Culture, 5(3), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.3167/nc.2010.050305

Tredici, P. Del, Ziska, L. H., Bunce, J. A., Ziska, L. H., Bunce, J. A., Hom, J. L., & Wolf, J .(2004). Green Blacktop

Campbell, L. K., Svendsen, E. S., Sonti, N. F., & Johnson, M. L. (2016). A social assessment of urban parkland: Analyzing park use and meaning to inform management and resilience planning. Environmental Science and Policy, 62, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.01.014

Nassauer, J. I. (1995). Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames. Landscape Journal, 14(2), 161-170. doi:10.3368/lj.14.2.161

Flowering Dogwood. (2019, September 8). Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://tree-map.nycgovparks.org/tree-map/tree/4137259

Roman, M. (2016, May 27). The Princess Tree: Stories of Paulownia. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://journal.rikumo.com/journal/the-secret-history-of-paulownia-wood

Editor, I. (n.d.). The secret of the Japanese Immigration stamp on your passport! Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://press.ikidane-nippon.com/en/a00088/

Paulownia. (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2020, from http://www.paulownia-it.com/en/paulownia-2/

Paulownia tomentosa (tree). (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2020, from http://issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=440

Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/pautom/all.html

Farmers' Almanac Staff. (2018, February 22). Possibly The World's Most Perfect Tree? Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://www.farmersalmanac.com/empress-trees-30577

Offsetting your Carbon Footprint. (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://worldtree.info/carbon-offsets/